Dogma Prize 2021: Introspection: Dogma Prize 10th Anniversary

2021 is a special year for the Dogma Prize, marking its decade-long journey with contemporary self-portraiture.

The theme Introspection – to look within oneself – has always been an intrinsic part of self-portraiture, but is now more resonant than ever considering the profound global upheaval of the past two years. Who are we? Do we play a role, where do we place, and what are our responsibilities? It is difficult to yield a comprehensive answer to these questions. In truth, perhaps we do not want an answer that is all-encompassing, but would rather seek out individual narratives from each of the exhibition artists. Imagine you are looking for someone with whom you can engage in deep conversation. This person may be a reflection of a friend, or a friend of a friend, or an acquaintance of a loved one. The journey to find that person might lead nowhere, but perhaps by chance you will find others who share an unexpected connection. Even if only for a short while. Who knows.

In this space, the eyes will look to an artwork, prompting the mind to lift the veil that shields another’s inner self. Hà Ninh’s intricate map conveys images of an interior habitat – the result of his looking inward and recalling through drawing the knowledge, judgements, and beliefs that are unique to him, without influence from other phenomena that exist in parallel. The artist asserts his individuality of thought amid a web of overlapping external influences, be they the weight of familial traditions, or certain delusions held by society. ‘I design my own set of languages, [so] that I do not fear the frames of reference imposed on me by existing languages, including that of my mother tongue. I’m also never afraid of being misunderstood, whether accidentally or intentionally.’

Coming on to Nguyễn Hải Đăng’s work, made from wood that was reclaimed from his childhood home, we gently step into the realm of faith to visualise his ‘introspection’ through the act of kneeling and questioning himself – a Catholic ritual that Hải Đăng has learned and practiced from a young age. As an artist, that ritual is intimately linked to his use of lacquer in the work, while as a Christian, he ‘becomes subject to self-commitment, self-honesty, and self-criticism, in an attempt to enter a Great Sacrament in Catholicism – the Sacrament of Confession, where [one] can be reconciled with God, with everyone, with [one’s] own self.’

To understand Prak Dalin, a young artist from Cambodia, let’s use signs – those that come from lines, forms, and materials – to communicate. Through her visual language and imagination, Dalin speaks of the Cambodian map, and of where she lives and her surroundings. ‘I merge abstract human forms standing in a row with their heads connected as one to form the body of a snake lying on the ground [...] The Snake, by all means, represents a character in society. The character of the snake not only points to a leader character, but also reflects on the Chinese millionaires who visit our land and take away what they need to fulfil their impulses.’

Then, going deeper into the space, we encounter Thuỷ Tiên / Sarah, who ‘at first [...] resisted “introspection” and the need to judge oneself as [she] created Anthropomorfish’, only to later admit that she ‘completely failed in doing so’. It is important to point out that while the mixed media installation seems harmonious and gentle at first glance, it is also bold. Thuỷ Tiên / Sarah used to emphasise that protagonists in movies are simply not real. Gradually, though, ‘I accept that protagonists can bring out the softest, most vulnerable parts of myself – parts that I would rather hide than show to others. [...] I am vague, I am romantic, I often get lost in abstractions. I am easily annoyed. I end up going round and round without being able to escape from old perspectives. I am sensitive. I know pain.’

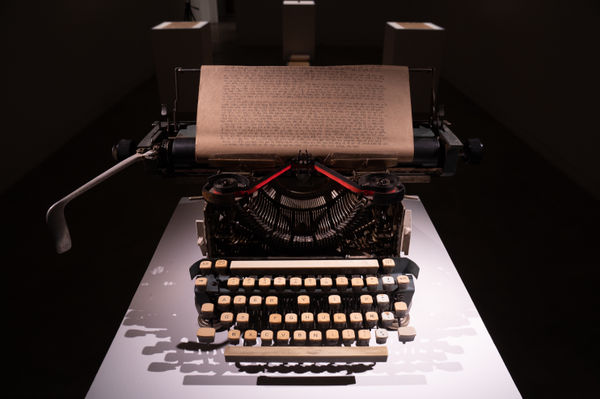

Also within the space, on another floor, our ears pick up the sounds from Đào Tùng’s work, which is closely linked to his ruminations on the Nhân Văn–Giai Phẩm affair. To the artist, ‘it is a “historical” event that, though brief, has inspired [himself] and many others with the courage, freedom loving spirit, and creative and academic desires of a previous generation of intellectuals and artists. An affair filled with sadness and regret not just for its participants but indeed for the entire nation.’

For Mao Sovanchandy, a young architect living through the upheaval of rapid urban development in neighbouring Cambodia, her identity is understood through a synecdochical use of portraiture: ‘I stand and hold up mirrors that reflect the contrast of the old buildings versus the new ones. My body becomes a faceless figure like many people and the city itself, which has lost its identity because of this fast-growing urban change.’

As a Western artist living in Vietnam, Léopold Franckowiak uses a personal story to demonstrate how human relationships transcend local boundaries. According to the artist, the ‘global dimension of the [pandemic] has the effect of giving painters an opportunity to immortalise what is happening to us and thus to make this painting part of History. And because History is always read in relation to other earlier and sometimes comparable events, I wanted to evoke another important epidemic: the Great Plague of Venice in the 18th century. This is what Harlequin’s costume refers to, with its two-coloured diamond pattern, used in the commedia dell’arte.’

Phạm Nguyễn Anh Tú’s video work is unconventional and colourful, yet sincere, heart-to-heart. The artist recalls his ‘consciously unconscious’ behaviour when collecting and storing certain thoughts and feelings that can be difficult to convey through words. ‘I was startled to realise the

connecting thread between my interests in memory and existence, and the passing of a friend around this time last year. Though their body no longer exists, elsewhere their presence was recorded, forever archived in photographs and rolls of film. And those photographs and film rolls are the coming together of countless pixels.’

In Ở đâu vui ở đó có Bê Đê, we observe ‘a reflective journey on gender identity and expression rooted in personal experience and observations on how society imposes certain standards on minority groups.’ Jack!’s story is a personal one, but he hopes that its language could also ‘send a larger message, and in the end serve the purpose of creating for oneself, and not for anyone else.’ A famous philosopher once said that thought does not exist without images. In other words, our own pool of experiences is only available to us. Others who wish for access must rely on the visual signals that we emit. In this exhibition, the artists have transformed images of introspection into multi-dimensional, cultural images. How will the viewer receive the artists’ processes of mental labour to create artistic meaning? Hopefully, through imagined dialogues, each of us can come up with an answer of our own.

Bảo Châu.

-

![Hà Ninh Phạm, D6 [Shrimp Pond], from the project My land, 2020](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Hà Ninh Phạm, D6 [Shrimp Pond], from the project My land, 2020

Hà Ninh Phạm, D6 [Shrimp Pond], from the project My land, 2020 -

Đào Tùng, -- --, 2021

Đào Tùng, -- --, 2021 -

Léopold Franckowiach, Self-portrait with Columbine, 2020

Léopold Franckowiach, Self-portrait with Columbine, 2020 -

![Nguyễn Hải Đăng, The Confess[i]onal , 2021](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Nguyễn Hải Đăng, The Confess[i]onal , 2021

Nguyễn Hải Đăng, The Confess[i]onal , 2021 -

Prak Dalin, Merge, 2020

Prak Dalin, Merge, 2020 -

Mao Sovanchandy, Asymmetry, 2021

Mao Sovanchandy, Asymmetry, 2021 -

Phạm Nguyễn Anh Tú, Nguyễn Thị Điểm Ảnh, 2021

Phạm Nguyễn Anh Tú, Nguyễn Thị Điểm Ảnh, 2021 -

Thuỷ Tiên (Sarah), Anthropomofish, 2020

Thuỷ Tiên (Sarah), Anthropomofish, 2020

![Hà Ninh Phạm D6 [Shrimp Pond], from the project My land, 2020 Pencil, acrylic and ink on paper 123 x 260 cm](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_800,h_800,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/dogmacollection/images/view/171822f5ad324e304428c5c5b9919055j/dogmacollection-h-ninh-ph-m-d6-shrimp-pond-from-the-project-my-land-2020.jpg)

![Hà Ninh Phạm, D6 [Shrimp Pond], from the project My land, 2020](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/dogmacollection/images/view/da8741a8ef7737201e94e266daa087c8j/dogmacollection-h-ninh-ph-m-d6-shrimp-pond-from-the-project-my-land-2020.jpg)

![Nguyễn Hải Đăng, The Confess[i]onal , 2021](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/dogmacollection/images/view/a83d0cc1666747f85eea9446bbd08879p/dogmacollection-nguy-n-h-i-ng-the-confess-i-onal-2021.png)