Our Address

27A Nguyễn Cừ, Thảo Điền, Quận 2, Hồ Chí Minh City

Open by appointment

Open by appointment

Contact Us

Follow Us

Hard power and soft power go side by side, and one cannot exist without the other. Subtle and more sophisticated acts of control appear in the form of education, the arts and communication. In a modern society, having a conscious awareness of knowledge as power is essential for a sustainable development. It is also crucial for any head of an authoritative state to realise that having the right direction of knowing is, indeed, more important. Education becomes the utmost matter, where special attention needs to be direct. In Vietnam, elementary education is compulsory, as stated in the Constitution. Also as further stated in the constitution, the aim of education is to "train the socialist workers and cultivate the next revolution generation." Students are supposed to join the Pioneer's Organisation and Ho Chi Minh Communist Youth Union. In the classrooms from elementary until high school, students are to be greeted with Ho Chi Minh portrait and "The Five Things Taught by Uncle Ho." Patriotism is taught inside the national education curriculum. University students, regardless of major, will take Marxism-Leninism as a compulsory course.

Art students are to be taught Marxism ideology on top of studio courses [2]. They are also assigned to live and work with farmers and the indigenous community in new economic zone or remote areas, so as the purpose is to understand the society and incorporate the society to art, as one of the characteristics of socialist realist art. Cinema, literature, music and other studio art forms are under the direction of their corresponding associations, which are under the direct control of the government. Before the amended constitution in 1991, literature and the arts had to "adhere to Marxist-Leninist ideology, to educate [the people] the state and the Party's policies and direction, and enhance the love for the revolution…" [3] This leads to the third category of soft power: communication. Since public media have the message-delivering purpose, they carry the responsibility to propagandise, to direct and to influence. Public speakers are to be installed in each tổ dân phố that deliver different programmes on certain hours of the day. In each ward's communal area there will be a bulletin board that necessary information is posted on. Propaganda posters, slogans are a part of the communication plan. Starting from the wartime until peacetime, propaganda serve as a tool to consolidate patriotism, enhance the government's total war policy, as well as to encourage industrial and agricultural production. The rest of the essay will investigate more on the different characteristics of propaganda and what make it, in the context of North Vietnam, as an excellence as an art form and a communication strategy.

The characteristics of propaganda and the communication's tactics

Jacques Ellul argues that propaganda follows the technique that has an effect on individuals as a totality, in order for its law of efficiency to work. The propaganda systems have evolved, since the end of World War II, into the major three groups, according to the prominent political powers at that time. The first one was modelled after U.S.S.R, which included Eastern Europe, East Germany and North Vietnam. Then there were the United States, Western Europe, South Korea and South Vietnam. And then there was China.

Propaganda takes in many different forms, including broadcasting and illustrated messages, and directed towards different groups of audience. Ellul discusses in his book, Propaganda, The Formation of Men's Attitudes, in order to perform its full effectiveness, propaganda carries both external and internal characteristics, with external characteristics direct towards the message receivers, as well as the organisation that create it, and internal characteristics belongs to the fundamental psycho-sociological base that creates foundation for propaganda to exist logically.

Firstly, propaganda appears to be total and its messages direct to both the individuals and the masses (Ellul, 6). The individual, e.g. an ordinary citizen, cannot be treated as the specific individual but is to be reduced into an average. An average citizen is deduced from a mass of individuals that share the same living, political and economic environment. The purpose here is not only to ignite a uniform belief but also to form and influence a collective's action. In this case, when an individual is treated as an average sample, he is reached by the propaganda whilst still enclosed within the mass entity. The propaganda sends its messages to an assembled collective of people, yet reaches each individual by creating an impression of a personal message. In this case, the use of plain folks methodology is needed in order to create an assumed common sentiment shared by every member of the mass.

figure 1.0 (from the Dogma Collection)

Take figure 1.0 as an example. The poster shows in the foreground an image of a seemingly guerilla fighter holding a bamboo-liked weapon, next to him, in the middle and background are a southern woman, as telling from her checkerboard head scarf, armed with a trifle and another soldier without a clear face. Painted on the assumed yellow wall is quoted words from Nguyễn-văn-Hiếu, saying: "If needed, our children and grandchildren will continue to fight." Since there is no title prior to his name, we would assume Nguyễn-văn-Hiếu is an ordinary man, who perhaps also appears to be the depicted guerilla fighter. In this example, the propagandist uses an individual with the intention to talk for a group of people, either it is for either a group of fighters, soldiers, their relatives, if not all. A high-powered statement from an ordinary man appears to be more effective to those groups than a powerful leader's. One can find him(her)self being touched by such words. "If needed…" - who needed whom? The country? Peace? The people? "I am needed, our children are needed." An ordinary person finds him(her)self carrying such an obligation, and it is for a good cause. The attires of the man and the woman in the poster also are relatable. They are humble and vernacular to the people, who belong to the working class, who live in the rural. In this case, the propaganda has clearly revealed its intention of approach: to talk to the rural population, to justify the act of elongating the war, and to engage and recruit support for all those war policies.

The second trait of propaganda, according to Ellul, which creates a normalcy in the every day's life, is its use of total media, including the press, radio, television, movies, posters, meetings, etc. During the Vietnam Civil War, there was a radio programme that was rather popular with the American soldiers. It was hosted by a lady named Trịnh Thị Ngọ, also known as Thu Hương (Autumn's Fragrant), the radio called Hanoi Hannah broadcasted English-language content towards the American troops in South Vietnam.

"How are you, GI Joe? It seems to me that most of you are poorly informed about the going of the war, to say nothing about a correct explanation of your presence over here. Nothing is more confused than to be ordered into a war to die or to be maimed for life without the faintest idea of what's going on." (Hanoi Hannah, 16 June 1967)

In its total policy, each medium of propaganda carries its own purpose of penetrating and encircling the public, however, in order for propaganda to reach every nexus of the society, in both sociological and psychological perspective, all media have to be utilised at the same time. Movies and interpersonal contacts work in penetrating around and within the social climate, with slow and progressive effect whilst meetings (tổ dân phố meeting, local Party's members meetings, etc.) and propaganda posters tend to ignite immediate temporary yet intense actions. Printed press and radio in the local language help to cater news shape general view domestically (the use of neighbourhood's public speakers, and local newspaper like Báo Nhân dân, etc.), whilst foreign language press and radio programme aim for international action and impression. During the Hanoi Hannah programme, sometimes Thu Hương would read messages from the anti-war Americans, amongst with other news on casualties, to emphasise the unjust involvement of the US in the war. The strategy is to use the enemy's language to soothe the enemy's soul [4]. The success of propaganda cannot not be total and satisfying unless members of enemy become the sympathisers of the propagandist's regime.

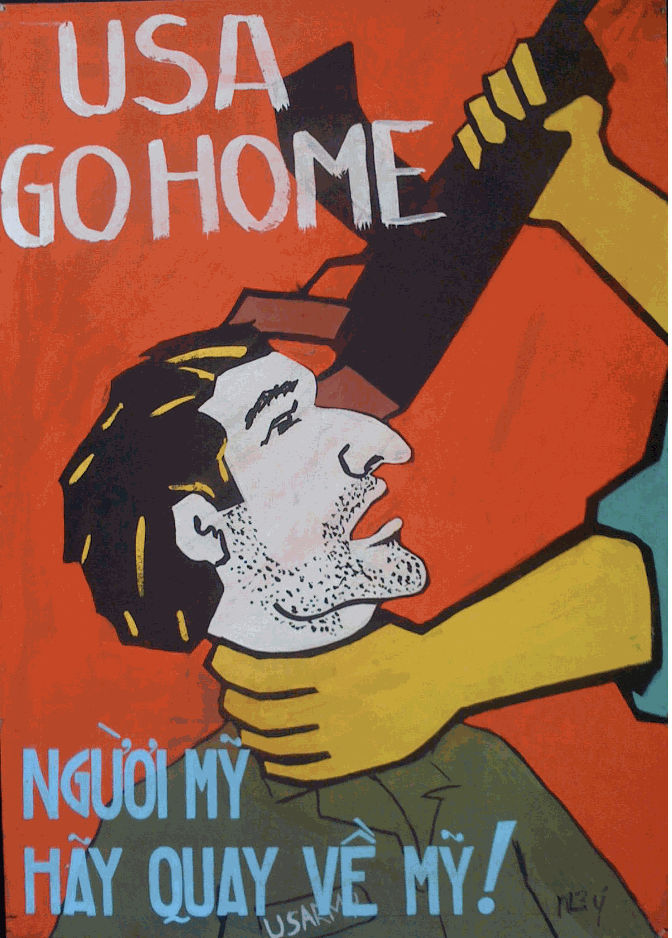

figure 2.0

Stop going to Vietnam

(from the Dogma Collection)

figure 2.1

American go back to America!

(from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 2.0 has more tendencies to appeal to international audience than domestic, whilst figure 2.1 can be effective in causing strong emotion towards the local public. Figure 2.0 depicts seemingly Western intellectuals in front of anti-war protests in both French and English, given the international pressure on the US's involvement in the war was rather prominent in the 60s and the 70s. Western artists, intellectuals and philosophers including Noam Chomsky, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel Foucault, etc., and socialist sympathizers criticised the politics behind American troops in Vietnam. Figure 2.1 endorses more satisfying in the action of defeating such troops, with the use of simple and straightforward English, which might appeal more to the domestic viewers. It is to justify one violence against another violence, to direct more towards action than thought. The purpose of total propaganda is to make it continuous without leaving the people anytime to question its logic and rationality.

In order for propaganda to work effectively, an organisation ought to exist to give propaganda its structure, to control the mechanism of mass media. Ellul calls the organisation behind propaganda "the technicians of influence" (Ellul, 20) that gives instruction for what medium to be used at what circumstance. As mentioned above, propaganda has to cause an impact on both sociological and psychological level. The use of an organization is strongly associated with the other two components of soft power: education and the arts. The control over how propaganda is made, which artist to recruit and remove, to where it is distributed and which subunit is in charge of what, belongs to the Central Propaganda Department (Ban Tuyên Giáo Trung ương), or the equivalent in other countries. The power hierarchy of Communist Vietnam ranks from the Central Committee (Ban chấp hành Trung ương Đảng) at the top of the power funnel, followed by the Politburo (Bộ chính trị), Secretariat (Ban bí thư Trung ương Đảng) and the Central Military Commission (Quân ủy Trung ương), which are the highest body of the Communist Party of Vietnam that are in charge general orientation of the government and enact the policies onto their subunits. Central Propaganda Department (CPD) receives order directly from the Politburo to circulate to other subunits, include all the ministries of culture, propaganda, publication, education and training, etc. Education and the arts not only produce a strong workforce for making propaganda, but also enforce a secure sociological fundamental within the receiving public. Since the most important objective of propaganda is not to leave one any thinking gap for doubt and reflection, it is important for any propaganda organisation to construct a structural scheme from indoctrination (education as pre-propaganda) to sustain an action. All media, again, are to be utilised in order for the Department to control over how the messages of the propaganda be transferred. Cinema, music and literature become covert tool to build infrastructure for the spectator of the propaganda by existing in one's consciousness every single day. On the other hand, public propaganda such as posters and meetings are meant to influence one's action on top of an already built public allegiance. The Central Propaganda Studio located in Hanoi was one of the leading studios that produced high-quality posters during the war. It was officially founded in 1968 after the National Propaganda art Exhibition. Central Propaganda Studio (Xưởng tranh cổ động Trung ương) belonged to the Information Bureau, and has been active in producing posters for several economical and political campaigns.

According to Dương Ánh, an artist and deputy director of the Studio, direct mandate would be sent from the Propaganda Department when it came to important political campaigns. It was important to make the messages clear and strong enough to incite actions from the public [5]. The Studio would hold open calls for propaganda art creation from time to time, and a lot of artists as well as art students participated as a chance for their works to be exhibited. Since the royalties from the exhibition would aid their expenses on art supplies, a lot of artists came to propaganda as a way to sustain their practice.

In most of the posters made during the war, there are two prominent methodologies being used that reaffirm the orthodox of propaganda: the use of conditioned reflexes and the use of myths. The theory of conditioned reflex was founded by a Russian physiologist named Ivan Pavlov. It is the most basic form of primary learning, which associates the events with action through the use of symbols [6]. The average citizen is to be trained into recognising various symbols and is incited into needed action by the propagandist. The symbols can be either glittering words, ad hominem, or the method of transfer, in which the person is tied to an idea by the use of powerful visual.

Figure 3.0

Followed Uncle's call, We enlist to protect the country

(from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 3.1

Nothing is more precious than Freedom and Independence

(from the Dogma Collection)

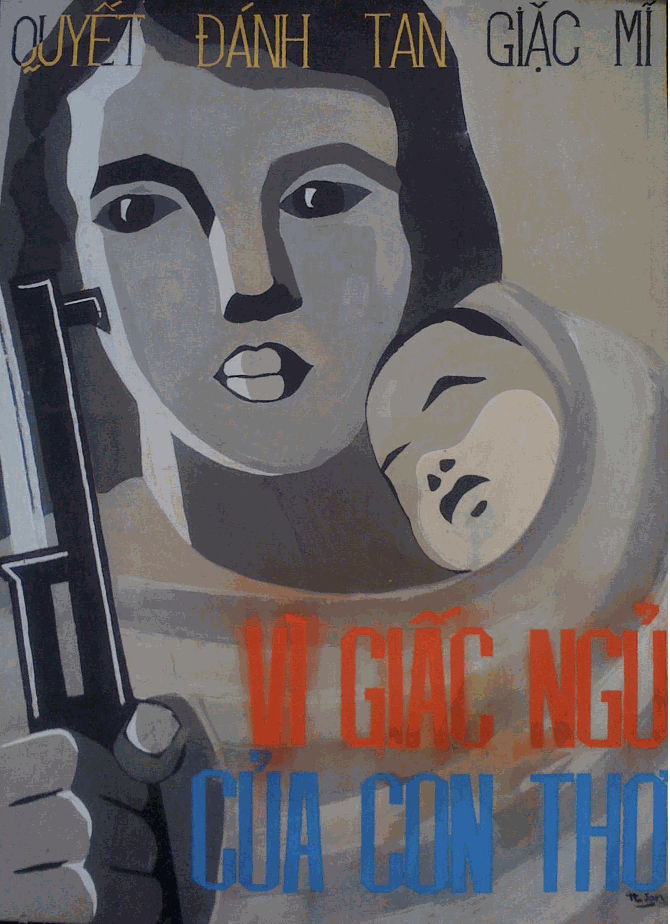

Figure 3.2

Determined to fight the American invader, to protect the children's sleep

(from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 3.0 and Figure 3.1 both associate the image of Ho Chi Minh to the action of army enlistment to fight for an honour. Figure 3.1 uses the words "liberty" and "freedom" that have strong honorific emotional ties to the citizens. What could be more honoured than to fight for the "liberty" and "freedom" of a country? Moreover, given the quote is from Ho Chi Minh, "nothing is more precious than liberty and freedom," the use of both his image and sayings produces an absolute symbol of Ho Chi Minh, as a patriot, a leader and a compass for young people to follow. Figure 3.2 uses the word "giặc," which can be understood as either "enemy" or "invader" on top of a strong contrasted black and grey with a small shade of colours on the baby's face. The image of a sleeping baby (representing peace) contrasts the grey-colour tone of the painting (represent depression, something bad) provoke emotion: sympathy towards the innocence and anger towards the offender (the giặc Mĩ - American invader). Figure 3.3 utilises the images of two dark-coloured skin figures to depict the American and South Vietnamese soldiers, in which the American figure rides on top of a South Vietnamese (the figure wears a pair of trousers that resembles the South Vietnam's flag). They are both crawling on a ground that is full of graves. On the front ground, there is a woman holding a child, with a stringent expression, accompanied by two questions: "Who will win? The world supports whom?" "The world" becomes a verbal symbol for an international just, and the propagandist appears to speak for the good, the orthodox. Here, the method of association creates the condition as the symbols that leads to the reflex as the cognitive separation of the good and the bad. It is strategically important for the propagandist to develop the good into myth, to ensure the vision in which men will live become vivid and lively enough. Those images, be they the fair and peaceful society, the high-rise buildings resulted from industrialisation or a rice field with hefty crops, become the collective myth that bring promise and positivity.

Figure 4.0

Industrialisation for economic development and life advancement

(From the Dogma Collection)

Figure 4.1

All ethnicities are equal

(From the Dogma Collection)

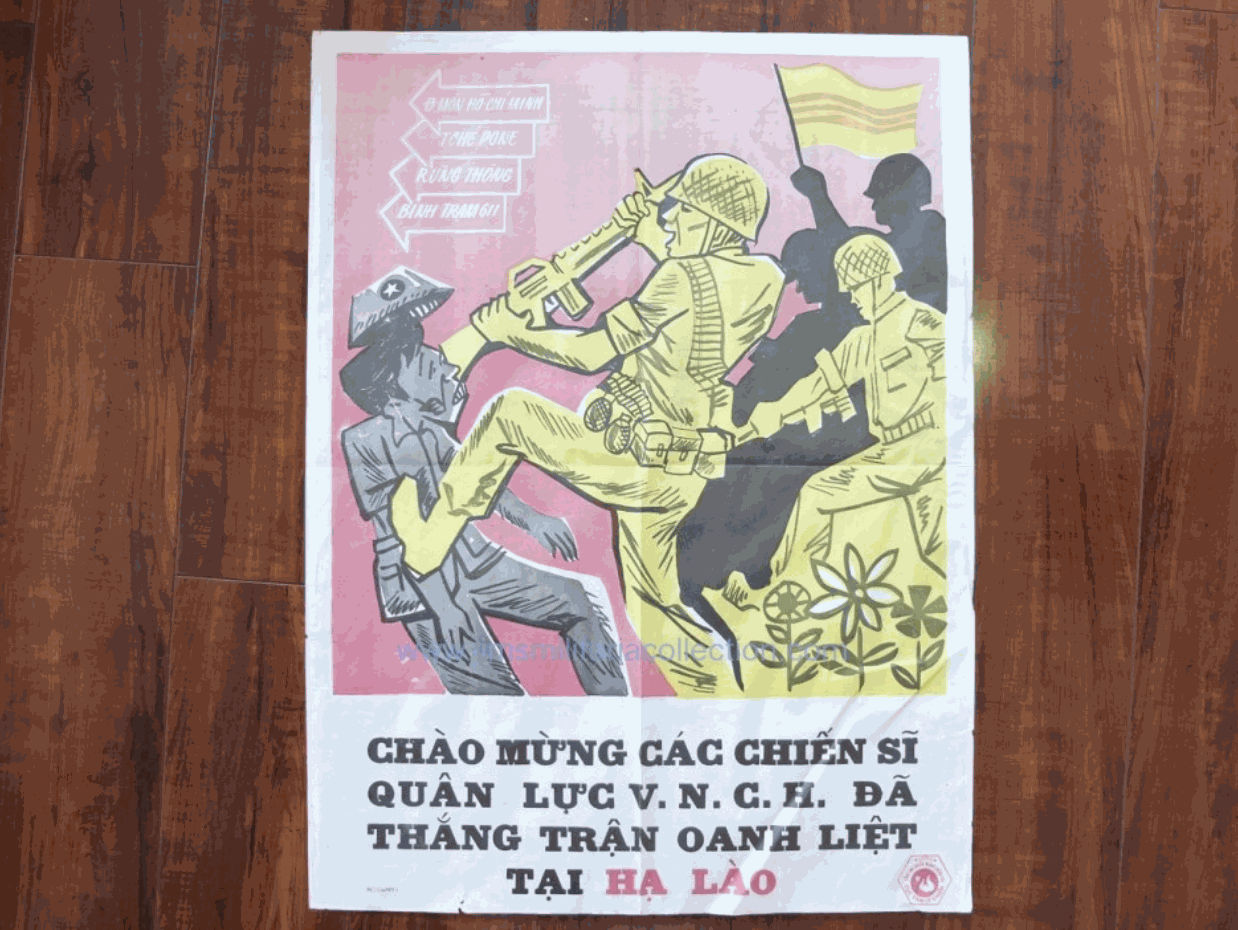

Figure 5.0

Congratulations on the victory of the soldiers of ARVN at Lower Laos (from Jim's Militaria Collection [7])

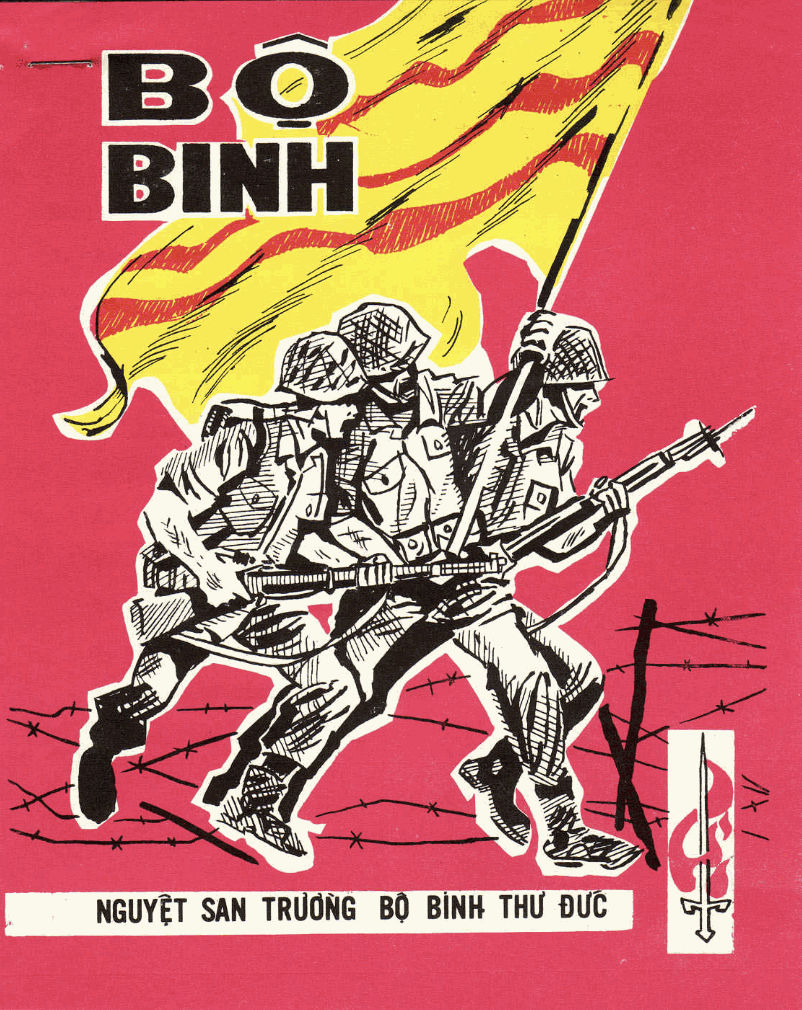

Figure 5.1

Infantry - Thu Duc Infantry Monthly

(from: http://www.psywarrior.com/VietnamOBPSYOP)

Figure 5.2

Uncle Ho's good children, clear up the road to save the country (from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 5.3

Wherever there are enemies, we shall go (from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 5.0 and 5.1 are posters from South Vietnam, which depict images of soldiers from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN - Quân l ực Việt Nam Cộng Hoà). Figure 5.2 depicts the image of soldiers from the People's Army of Vietnam (PAV - Quân đội Nhân dân Việt Nam) and 5.3 is a portrait of a female soldier from the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (or the Vietcong - Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam) in front of a line of the marching PAV soldiers. Although the subject matters are the same (the soldiers), their representations are not. Whilst the North Vietnamese soldiers are illustrated to be wearing modest and ordinary attire with sandals, ARVN soldiers are shown off to more sophisticated clothing, boots and weapons, which are more associated with the American army than Vietnamese culture. The image of ARVN soldiers, then, fall more into the North Vietnamese government's narrative of being American's mercenaries than the their own description as pure Vietnamese soldiers. Vietnamese people, after more than a hundred years of being colonised, would tend to feel more connected and sympathized towards the North's objective of clearing foreign invaders (giặc Mĩ) out of Vietnam. For the North Vietnamese viewers, the propagandists do not need to sow another new ideology to justify their fight in the war, whilst in the South, it is inevitable that there are criticisms towards the intention of the American involvement in Vietnam that might results in corruption and other economical dependency. In the South, the act of accusing Communism, which is a political ideology, can only appeal to those who have already been against Communism, whereas, the act of accusing foreign invaders and arouse nationalism speaks to almost every one in the North (and even in some parts of the South), given the circumstances at that time. Understanding the collective presuppositions (happiness, independence, freedom) and expressing the myths (happiness, nationalism, heroism, world harmony…) have to go hand in hand in a creation of the propaganda. It has to be clear and on point yet vague enough not to raise any doubts.

Another principle that the propaganda needs to follow is timeliness (Ellul, 43). The public is more connected with immediate event than something belongs to a distant past. Whilst propaganda serves a different purpose from the news, the recent event will be the catalyst for the message to take into effect.

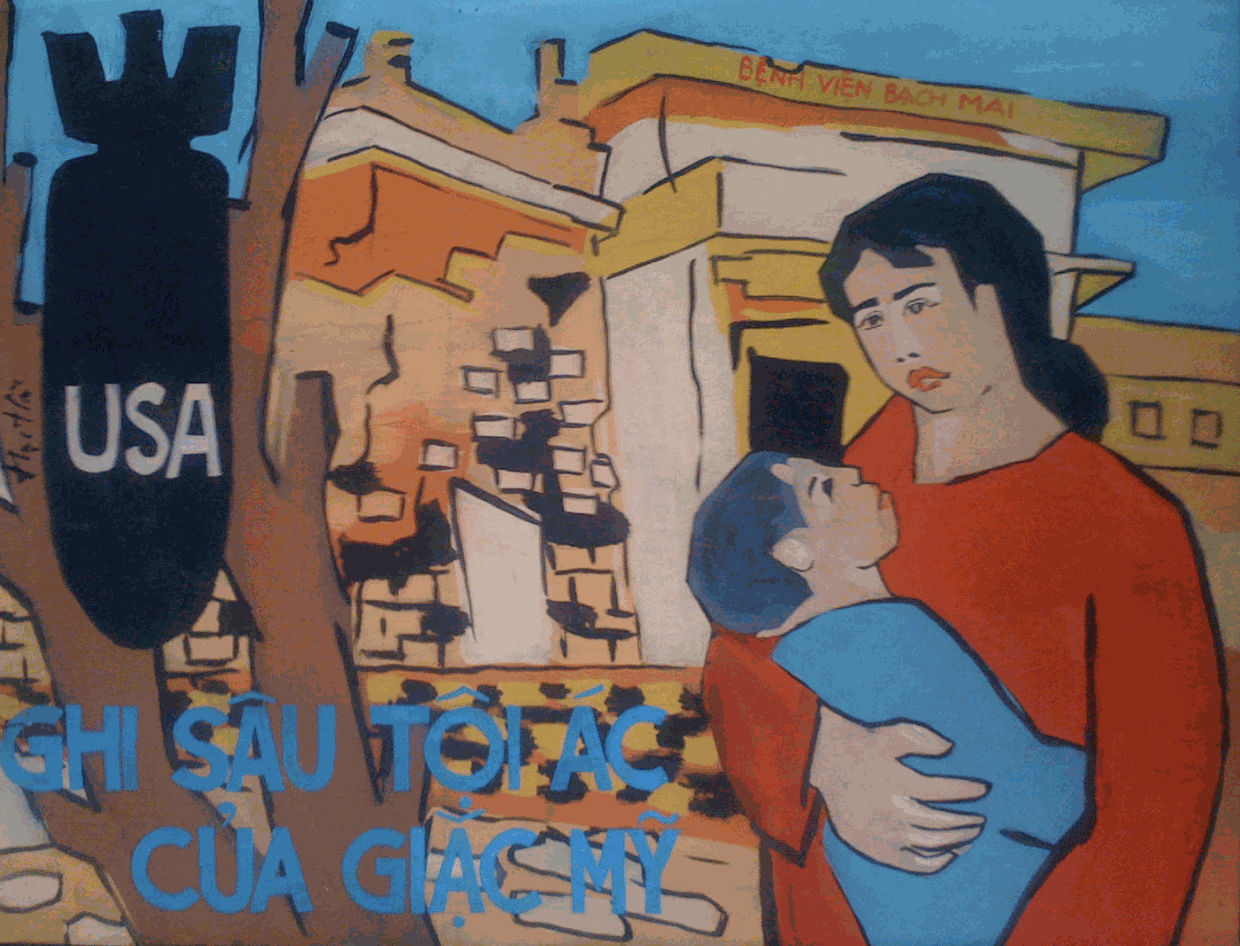

Figure 6.0

Deeply remember the crime cause by American enemy. (from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 6.1

3243 American aircrafts have fallen (from the Dogma Collection)

Figure 6.0 and 6.1 refer to the year 1972 when American aircrafts bombed the North with B52. In figure 6.0, a woman holding a baby in her arms, they are standing in front of Bạch Mai hospital that is damaged by the American bombs. What distinguishes these illustrations from a news report, given that they are both informative, is the predetermined emotion towards the culprit. Here it is even more justifiable to feel anger towards the enemy because these posters follow the bombing event right away. The propagandist becomes one of the people: he speaks to and speaks for them, his words are their words, and his emotions are their emotion. From there, any call for action will be more effective, with little to no time for doubts or objection, thanks to the timely sensitivity.

Another important aspect of propaganda is its spectator. What kind of spectator does propaganda aim to? How is the spectator of one medium distinguished from the other? And how aware are the spectator that they are viewing propaganda instead of facts and truth? The propagandist understands that it is impassable for mass propaganda to reach the well informed and the opinionated population. His spectator must be comprised of undecided citizens and manual labourers, which make up the majority of most developing countries or nations are in a political chaos. North Vietnamese art students are sent to remote areas to live and work with the locals in order to understand their needs (Nguyễn Lan Hương, personal communication, August 28, 2018). Propaganda artists often make field trips to places, where the topic needs to be addressed on. The spectators of propaganda are expected to share the same concern of their fellow citizens. However, they cannot be too exposed to the intellectual world, where presumptions are always questioned, hence the need for freedom from authoritative control. Those who already support the cause do not need to receive the messages, or to be convinced either. They serve different purposes in complement with the propaganda: they watch, control, educate and even actively involve in propaganda making process. The targeted spectators need to be distant from the complicated arguments on philosophical and moral questions, yet remain in touch with the collective experience, where the shared feeling ranks from strong to intense in emotion. In this case, the more oppressed and isolated the population, the more effectual the messages become.

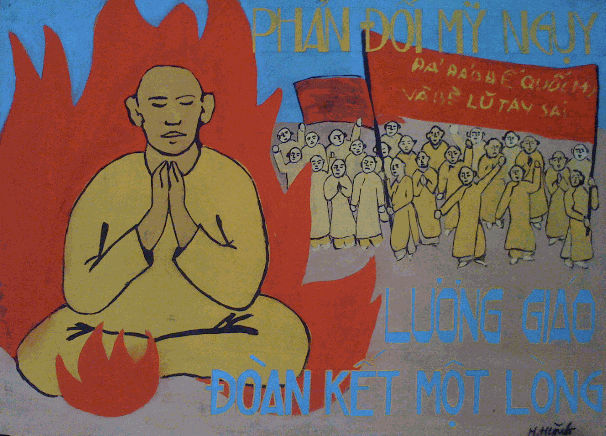

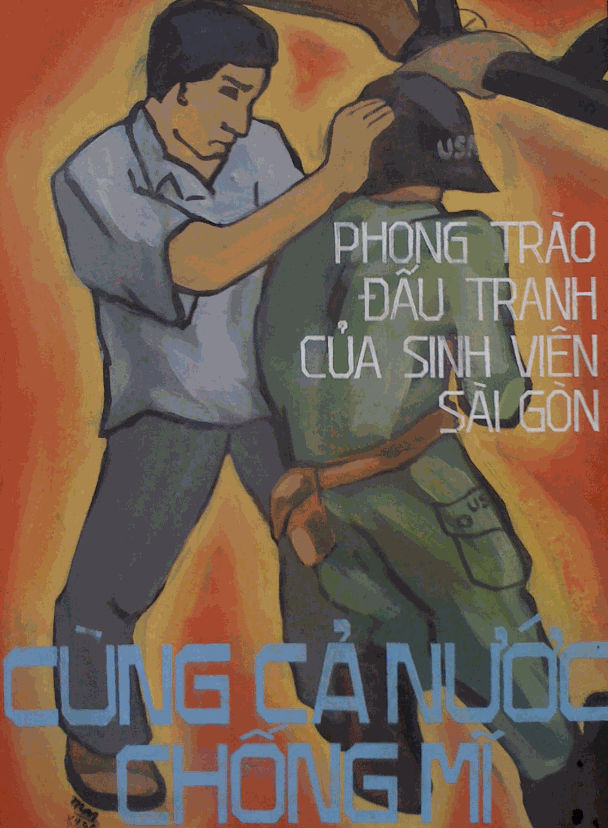

Figure 7.1

Resistance movement of Saigon's students, together with the nation to resist against the American (from the Dogma Collection)

Both figure 7.0 and 7.1 refer to events and movements happened in the Saigon, however, the spectators for those illustrations are not those who directly mentioned in the propaganda. The spectators might not even Southerners but people who live in a remote and isolated place from the South, who might not get accessed to news or analysis on what happen at the other side of the country. Hence, the propaganda is both informative and reaffirming. The key methods here are to present events out of their context, and impute meanings to them. It is unnecessary for Northern spectators to understand the complexity of the students movements in South Vietnam. But it is essential to show proofs that there is resistance, and fill them in a certain narrative that the propagandists have planned at the start. The spectators might be made to believe that it is true that the other side of the country is under oppression, and it is obligatory to fight against the invaders. There are nationalism, heroism and aggression to be provoked. Once there are enough justifications, actions are expected to happen: the support for total war policy.

Archiving the propaganda as research materials | suggestion on looking at the archive

The Vietnam Civil War has ended in 1975, and Vietnam has become a unified nation under one political and economic system. In 1985, the Central Propaganda Studio merged with the Central Fine Arts Studio to become the Central Fine Arts Company. According to Thục Phi, the director of the former Central Propaganda Studio, the some of the posters were archived by the Museum of Revolution (now has merged with the National Museum of Vietnamese History). However, the rest of the posters remain unknown [8]. The National Museum of Vietnamese History in Hanoi claims to have the most complete and diverse collection amongst the national archiving centres in the country [9]. Along with the advancement of technology and its application into education, hand-drawn and hand-printed propaganda posters leave room for mass-produced digital graphic-designed posters, and LED political slogans. With the collapse of Soviet Unions, and the open up of the socialist states, research materials coming from those states are more accessible. Aside from being commodified as postcards and souvenirs for less than 20 USD, propaganda posters become a historical evidence of both an era of political conflict and aesthetic movement. The National Museum of Vietnamese History becomes the largest state-owned archiving centre, and in 2014, the Museum held an exhibition of propaganda arts made during the resistant war against the French. It is stated in the Museum's website that the exhibition hopes to give a more truthful, and deeper understanding about the resistant war on the French [10]. The archive in this case serves as a semi-public resource, which opens on a certain occasion to narrate a particular topic. According to Foucault, an archive is either "a sum of all the texts that a culture has kept upon its person as documents attesting to its own past, or as evidence of a continuing identity," or "the (physical) institutions, which, in a given society, make it possible to record and preserve…" but it is instead the law to control what can be said, it is the "system of its functioning" (Foucault, 129). The archive becomes the "knowledge" whilst taking possession of it grants "the power" to its proprietor. Foucault argues that the notion of power/knowledge can never be independent. Let's take the National Archive of Vietnam as an example. In order to receive a research material, an individual needs to follow a strict ladder of procedure that is an exchange of power-knowledge. The first step is to provide personal identity card, official request document, or official reference letter (power), in order to open reader's account. The reader then proceeds to fill in the form of request (power) that is going to be reviewed, examined and approved by the manager, and the director of the National Archive, or the department head of the National Department of Archives and Document if the requested documents are from the restricted category (power). Only when all the forms are approved does the reader's request be transferred to Preservation's Room. He will then receive his desired research materials (knowledge) [11]. Is the individual the proprietor of the knowledge now? Can the individual seek knowledge without going through the hassle of proving himself to the knowledge's proprietor?

Here, it raises another question of the legitimation of knowledge, its credibility on the ever-evolving technological world of digitisation and reproduction. What is knowledge and how can an individual utilise it in the post-modern society?

Lyotard argues in "The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge" that since World War II, thanks to the advancement of techniques and technologies, people have outgrown of the needs to have meta-narrative, or the grand narrative. It is note-worthy to understand and accept that grand narrative or the knowledge as an epic brings the State its credibility (Lyotard, 28). Knowledge, according to Lyotard, is not only "a set of denotative statement," but a competence of "know-how" that transcends the notion of truth, that includes technical qualification, wisdom, aesthetics (Lyotard, 18). The problem for an individual when looking for knowledge in a non-governmental institution is the unproved legitimation or the questionable credibility of those sources. In which criteria a statement becomes scientific knowledge? The legitimation of knowledge here is a process through which the "legislator" of the scientific discourse determines the conditions and criteria (the language-game [12] - or professional terminology) to examine if a piece of information has fulfilled in order to be in the grand narrative (Lyotard, 8). Then there's a need for the acknowledgement of the micro-narratives that contribute the knowledge in their own languages . That leads to, alongside with the national archives, the participation of private archive, personal collection, library, and the use of arts and documentaries as archives. The de-centralisation of knowledge is a natural and necessary act as long as an individual is active and aware of the knowledge he is seeking.

There should not be a rigid methodology of looking at an archive, be it the state-owned or private one. A propaganda art collection, for instance, can be looked at from various perspectives: political, diplomatic, communicational, psychological, aesthetic, thematic, educational, or even its international influence as an art movement (protest art or resistance art). The readers are encouraged to have a more active role in approaching interdisciplinary subject (in this case, it might be art and politics, or art, psychology and communication), which reverses the dictated relationship between the creator and the spectators, or the message sender and message receivers. Foucault's model of knowledge-power can now be de-centralised; also the grand narrative can be de-legitimated, so that the private ownership and personal transference of knowledge have the rationality of legitimising themselves.

The essay has addressed the politic of communication, and questioned how sociological and psychological preparations have helped to deliver the messages of ideology. Propaganda art is a special subject that needs to be paid more attention than just the mere surface of art or politics; it belongs to the middle zone of political science, with all of its abstraction, and mass consumption. Vietnam has gone through a long tunnel of conflicts that assuredly can be analysed and reflected through the lens of art and culture. Thanks to technology development, researchers today have more democratic choices of approaching and processing the desired materials. This essay is nothing but a humble introduction to one possible way to look at the art of propaganda, and the propaganda art, which hopes to set a premise for future researches from various angles.

Works cited

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.