Our Address

27A Nguyễn Cừ, Thảo Điền, Quận 2, Hồ Chí Minh City

Open by appointment

Open by appointment

Contact Us

Follow Us

It has been 52 years since his passing, yet he is still omnipresent in contemporary Vietnam: his face on all the banknotes, his portrait accompanied by a five-rule doctrine in every classroom at public schools, his burst in government-owned institutions, his life-sized (or sometimes grandiose depending on the city's financial budget) statues in town squares, his birthday anniversaries are celebrated every year on every possible media channel - online and offline, cultural products about him or inspired by him are getting released and revisited every now and then, his narrative re-investigated by both local and international scholars. Most importantly memories about him, whether first-hand experience or hearsay are still vividly remembered by a large group of citizens, who lived through a part of the Vietnam war. His altars with constantly burning incense sticks can be found in institutions, at homes with dominant position over one's ancestors, or even dedicated shrines and temples. He is Hồ Chí Minh or widely regarded as Bác Hồ or Uncle Hồ - the "elderly father" of the compatriots, who founded the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. With such hyper-symbolic presence in both public and private realms, he is worshipped like a god but unlike any gods that we know of, he represents and valorises a political ideology: communism. This phenomenon is often described as a political religion in which Hồ Chí Minh is its cult of personality, a term describing "the practice of non-democratic [socialist] regimes to promote an idealised image of a leader with the aid of modern mass media in order to generate personal worship in a society." [1] [2] Some of the notable personality cults are Lenin and Stalin in Soviet Union, Mao Zedong in China, Kim Il Sung in North Korea and Aung San in Burma. The Hồ Chí Minh's cult was initially created and tended by the man himself, however later he lost the control over his own image due to lack of political power as his successor, Lê Duẩn came into power in the 1960s [3]. With repetition and consistence, he adorns an image of a disciplined, modest and benevolent father figure reasoning that "a good example is better than a hundred lectures". [4] He speaks with no jargon, often uses popular proverbs and local sayings, while at the same tailoring his speeches for specific group of audience such as soldiers, workers, women and children. [5] His cult has garnered much attention from historians and researchers over the years, however most available scholarships focus on the analysis of his biographies, his writings and political strategies, as well as his testament and its posthumous execution. As the authoritative figure of the state, Hồ is no doubt the most popular subject matter in propaganda posters, which often appears with consistent and meticulous depiction as compared to the generally "robotic" human figures. [6] This essay will first explore how his cult was formed, then how the state has maintained and reinforced its form interpreted through public monuments, and propaganda posters dated from 1950s to 1990s.

Thach Hong Pham (2020) contends that the early signs of his charismatic leadership begun while he was living in France from 1911-1944. [7] It was during this time that Hồ took on the pseudonym "Nguyễn Ái Quốc" or "Nguyễn The Patriot" (or, literally, "Nguyễn who loves his country)[8], and displayed his Marxist and anti-colonialist worldview through myriad of published articles and treatises on French and International journals and newspapers. He was also the first Annamite activist to join leftist movements while he was here. As a result, Nguyễn Ái Quốc and his face frequently appeared on the first page of newspapers, and inevitably was elevated to the status of a martyr. [9] He was at the peak as a leader during the period from 1946 to 1956 for both his leadership as well as his public oration.[10] The year 1945 was both a crucial and iconic milestone for both the party and Hồ as its charismatic leader with reading the declaration of independence of Việt Nam at Ba Đình square marking the nation's transition from a colonial slavery to triumphant victory. The day since has become the country's official Independence Day.

At the time, with only 5,000 party members at hand,[11] the Communist Party and its helmsmen were still of little known to the mass. As a result, putting Hồ - a real person, with a rather inspiring life story on the pedestal would help make the party's ideology, objectives and future plans more accessible and widespread. One of the first steps of channeling all the adulation to Hồ was perhaps the distribution of Vignettes, Hồ's first (auto)biography penned by Trần Dân Tiên. Upon attending the 2/9/1945 event, Trần Dân Tiên was inspired by Hồ so much that he tried to schedule an appointment with him, and got to meet the president soon after. Though seeing a biography as necessary, the president turned down his offer as there were more urgent issues such as famine and country rebuilding at the time. Trần Dân Tiên however was not deterred by this, went on to write what historian Olga Dror called a "devotional piece of literature"[12] about Hồ Chí Minh - a patchwork of multiple personal accounts collected from people who had known or had met previously. In recent years, Vignettes's legitimacy as well as authorship were heavily contested and thought to be a work of propaganda by the state for there was no account on who Trần Dân Tiên actually was; at the same time, the book was blotted with a plethora of chronological and factual inconsistencies. Nevertheless, at the time the book was extremely popular as it was the first publication that could offer a detailed description on Hồ's life and political trajectory. It was also in this publication, Hồ begun to hail the status of the "Nation's Father" echoing the Soviet's patriarch archetype - as seen through the cults of Lenin and Stalin. In another reprinted edition of Vignettes few years later, he was referred to as Bác or Uncle - an appellation Hồ adopted in all communication shaping how his cult would take shape in the future, setting him apart from those of the Soviet leaders of which his strategy was modelled. As the Uncle of all Vietnamese, he is the elder brother of all fathers and thus he became the most powerful figure in the family. Also, in a letter to a doctor named Vũ Đình Tụng supposedly in 1948, Hồ affirmed his devotional pursuit of collective benefits rather than personal happiness stating that "I do not have a family, and do not have children either. Vietnam is the great family of mine". Altogether, his image has become that of an heirless Uncle, without a family of his own, who lives as a good example and brings a better future to his good nephews and nieces. Thus, according to Vietnamese tradition, it is their shared responsibility to give him proper ancestral worship. As a familial spirit with no association to any specific religion - the communist party abolished any religious affiliations upon establishment, together with his political achievement, the veneration of Hồ surpasses any Vietnamese heroes, and manages to infiltrate into every home and public institutions without any friction just like an all-encompassing deity.

In her book entitled "Cult, Culture and Authority of Princess Liễu Hạnh in Vietnamese tradition," Olga Dror notes that there are two important elements when examining a cult: form or the sublime, and content.[14] If form, she writes, is what makes people start worshiping a figure, ritual is its signifier through different modes of solemnisations. She goes on to explain the importance of ritual in the establishment and maintenance of a cult:

Ritual is a response to the awareness of utter difference, the difference between the divine and the human realms. It marks out a space separate from everyday life where humans are enabled to experience the sublime [emphasis added] and ''is, first and foremost, a mode of paying attention. It is a process of marking interest.'' Ritual is a mode of survival of the form, a bridge connecting it with the other part of the cult, which refers to discourses that position deities in different schemes of ideological affirmation [emphasis added]. These discourses can be literary productions, but they can also mark relationships between a cult and state authorities, be this through the symbolic conferring of honorific titles or through direct state sponsorship of the deity. These elements constitute the ''content'' of the cult.

Perhaps, Ba Đình square and the compound adjacent to it namely Hồ Chí Minh's mausoleum - or commonly referred to as Lăng Bác (literally Uncle's mausoleum), the Hồ Chí Minh museum, his stilt house and the One Pillar Pagoda, best illustrates the above-mentioned mechanism. Monuments make ideology and the state's legacy more visible as compared to other means of propaganda such as books, movies, due to its grandeur and prominent or history-laden geography. Once an idle land plot, Ba Đình square is now an icon of national independence as this historical site was where Hồ Chí Minh read the Declaration of Independence in 1945. The square, right in front of Hồ Chí Minh's mausoleum measures 320 x 100 metres with a capacity to accommodate more than 100,000 people is an ideal space for the state to hold public assembly. The square consists of two areas: one in front of the mausoleum, often used for military parade and for public use during off-duty hours, the other comprising 168 grass squares that are strictly guarded. In between these areas stand an enormous flag pole, where the soldiers perform flag hoisting and lowering rituals every morning at 6am and every evening at 9pm. It is worth considering the geomancy of the square and its surrounding monuments: instead of following the traditional North-South Axis, with the mausoleum situates in the west and the National Assembly right opposite on the east forming a connection between the sacrality and profane power.[15] Having the National Assembly in close proximity overlooking the mausoleum once again emphasises the symbiotic relationship between the state and its cult of personality, the nation and its guarding spirit. The sacred and the profane duality once again can be observed during the square's off-duty hours. Every day before 8am and after 5pm, the square is open to the public who are mostly joggers or pedestrians. My ethnographic observation of the morning ritual at 6am on 2/1/2021 recorded that some elder joggers showed up in pairs, some by themselves, some were chatting while they were carrying out their exercise, some decided to take a break by sitting and engaging in conversations with their on the sidewalk on the far left and far right. Without guards in military uniform doing a body and belonging scanning at the entrance, the atmosphere here is the same as any other public space. These casual activities will be interrupted once the soldiers prepare for the flag hoisting and lowering rituals. Pedestrians and joggers will be asked to stay clear off the pavement, behind a white line, and so some of them would retreat to the far corners of the compound or stand from the second row of the grass square area leaving the first row occupied by the soldiers. The entire ritual, with the drum sound as the cue, takes about 15 minutes in total. Afterwards, things resume to their previous state until the official opening hours of the mausoleum. Roaming in such a sacred and historical space, it is impossible that these pedestrians become completely immune to its symbolism and the rituals that keep the space performing. Such manoeuvre of space by the state in this case once again re-emphasises Hồ as the nation's benevolent ancestral spirit. Just like how an altar room in a family or a clan shrine while being imbued with sacred meanings, they could potentially become a playground for children or casual gatherings for the adults.

Locating right where his proclamation ceremony was staged, the concrete mausoleum, erected on the same date in 1973 - 4 years after Hồ's passing, with its plinths taking the shape of a lotus - an image that is synonymous to the late leader suggesting his association to the flower's myriads of good qualities such as purity, beauty, intelligence, kindness and generosity.[16] Every day, the site welcomes a massive influx of both local and international visitors, who hope to take a peek at Vietnam's founding father's embalmed body. By the time of my visit at the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, there were not many international tourists like before due to COVID-19 cross-border travel restrictions. Yet, the site was still packed with visitors from as young as a todler to senior citizen speaking in different provincial dialects. Entering from the main entrance on Ngọc Hà street, visitors stood in a line and moved slowly towards the mausoleum under the guidance of a soldier. At the doorsteps of the mausoleum, visitors were asked to turn off their electronic devices - for both security and sacred reasons. After one flight of stairs, visitors finally arrived at the room in which the body lies: the walk and the wait was long, while the actual personal experience one could have with Bác was brief. The dimness of the room, the distance one had to keep away from the thick glass coffin, and the perpetual advancement of the line (like that of a conveyor belt) render one's encounter with "him" as blurry and fleeting. I happened to stand behind a group of elderly "Uncle Hồ's soldiers" - a virtuous and intimate title given to cadres and soldiers of the Vietnam People's Army,[17] who travelled hundreds of kilometres from the central area of the country to pay respect to the man with whom they once risked their lives in spirit. As we approached the coffin, all the soldiers bowed their heads and started praying in a swift manner, someone from the group blurted out that their last wish had been fulfilled and other members nodded in agreement. The trip was indeed an emotional one for them, as we were ushered out of the chamber there was a prolonged solemn moment felt among the group, which followed them as they dragged their feet to Hồ's fishpond, his stilt house and the souvenir shop. I came back another day, following the same routine, however this time my group consisted of much younger visitors. As we reached the chamber, there were murmurs acknowledging the presence of Bác, as well as commenting on the authenticity of the corpse amidst children's cries and giggles. Such suspicion is not something new among the younger generation. Upon knowing that I had planned to visit the mausoleum, most of my Hanoian friends advised me not to go as it would yield nothing to visit a wax model. With the chemicals accumulated from the yearly embalmment procedure over more than 50 years, even a real corpse would not be able to retain its "natural" state. However, I find this suspicion to be unnecessary in this case given the fact that people from all walks of life in Vietnam as well as international visitors still find their way to paying respect to the body. Once a visitor sets foot inside the compound, he could not help but follows the protocol to act in certain way.

Not far away lies Hồ's namesake museum - whose architecture was too modelled off the lotus flower. Upon entering, visitors will be greeted by a larger-than-life statue of Bác waving at them from the heavenly sky. From here, visitors could take a turn on both sides of the statue, each way leads them to the exhibition area displaying artefacts of his life and political trajectory in a chronological order. Juxtaposing against the world's major historical milestones as well as local socio-political context with an emphasis on Vietnam's feudal and colonial periods, the exhibition functions as a materialisation of the text-based hagiography that has dominated the public discourse over the years. The exhibition - beginning with Hồ's family background and concluding with his altar - presents documents, writings, photographs, objects, personal belongings as well as clothing items in each location Hồ set foot on. An extensive number of artefacts together with sophisticated and impressive exhibition design seem to put exhibition-goers at awe and manage to convince them entirely from the first glance. Upon closer inspection, I realised the ambiguity of the label content as it is unclear whether the object on display is the original or a replica. The content of the exhibition, just like what is commonly known through Hồ's biography, conveniently leaves out some factual bias such as his family's scholastic background, his political misdeeds during Land Reform campaign in North Vietnam from 1954-1956 and the Tết Offensive in 1968. Thanks to the status of a benevolent uncle and leader, Hồ managed to deflect the criticism to his subordinates, and to preserve his image the curators of his hagiography have to be extremely cautious in the selection and presentation of information.

Amiral Latouche Tréville to seek way to liberate his country in 1911, is the Hồ Chí Minh City's branch of the museum. Much more modest in size and exhibition design, however, by the time I came here in May 2021 the place was in a state of idleness, probably due to COVID-19. While the first floor showcases mostly photographs, music sheets, artworks, individualised gifts for Hồ - mostly from the Southern soldiers, prisoners and compatriots, the second floor presents a brief overview of his childhood, his activist journey and his writings - a trickle down version of the one at Hanoi's branch. While these rooms offer the same sense of ambiguity, the display in the last room on the second floor illustrates one of the best forms of solemnisation of Hồ's cult. The room showcases a series of photographs as well as some miniature models and replicas of Hồ's altars and shrines in the the Mekong Detla provinces such as Tien Giang, Bac Lieu, Ca Mau, Soc Trang, Hau Giang and many more. The concept of North and South unity is extremely important in Vietnam's political discourse, as it was one of the main drives the state used to advocate for the liberation of Southern kinsmen. As such, the museum illustrates how during wartime Hồ, despite his old age and geographical distance, always yearns for the South stating that the land has always been in his heart; and the Southern soldiers and compatriots, despite many challenges and dangers, would still try to express their love for him through handmade gifts. Such strong North and South connection is later reinforced in the last room with an anthology of altars and shrines dedicated to him suggesting that citizens in the South always remembers him as their Uncle.

Two of the exhibits in the altar room on the second floor of the Hồ Chí Minh Museum in Hồ Chí Minh city.

In a publication on their collection of propaganda posters by the Military Museum, it is said that it was the August Revolution in 1945, which awakened Vietnamese artist's patriotism and guided them to the communist ideology. As a consequence, there was a competition in producing artworks, which criticised feudalism and colonialism among Hanoian artists at the time. In the end, the movement resulted in an exhibition of propaganda posters, along with mass distribution at prominent public spots in Hanoi. These artists later volunteered to contribute their "artistic weapon" to the fight against the enemy during the First Indochina War from 1946 to 1954. Their posters were either hand-painted or printed in large scale, and were put on display at trenches, military medical stations, worker's tents, on the walls of the village communal houses or on the People's Army newspapers published right at the battlefield. After the communist won the war, the Central Propaganda and Training Committee was tasked with creating effective communication to aid the party in their effort to reunite the North and South of Vietnam in the Vietnam War (1955 - 1975). The publication called this period as the peak for Vietnamese propaganda art during which time these posters have managed to reap both artistic values as well as effective propagandising.[19] At the same time, this period welcomed a younger generation of artists, who either received domestic education or had just came back from the Soviet Union creating a diversity in the work force and in their artistic creations. According to the museum, there is no liable statistical data on the exact number of posters produced, however the themes are varied from Tradition, The Glorious Vietnamese Communist Party, Beloved President Hồ Chí Minh, soldiers and compatriots going to the battlefield.[21] After the war, the message focuses on the rebuild of the country through agriculture, urban development and literacy campaigns. Until today, propaganda poster and banners are still visible in the country though clearly have departed from the hand-painted style of the past, and whose messages now focus more on public morality, public holiday commemorations and during important political events like the National Congress.

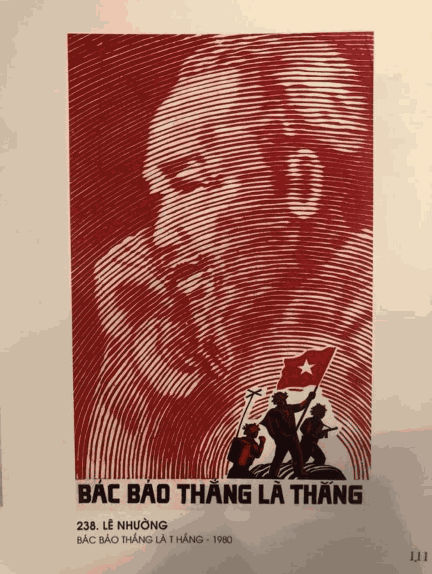

To unpack the iconography of Hồ Chí Minh in propaganda posters, I will adopt the analytic framework that is grounded on linguistic analogy treating the image as part of the visual language (lexicon and syntax), that all elements are interdependent. Depending on the importance of the campaign, the message is usually determined and issued by the Central Propaganda and Training Committee and the execution will be carried out by artists in the Central Propaganda Studio. Therefore, each production will be carefully vetted before going public, and so both of the content and images in propaganda posters are strictly regulated and supervised by these two offices. He is known as a loving uncle to the compatriots and a steel leader to the enemies, however the portrayal of Hồ in propaganda posters only focuses on the first archetype when he was in his 60s and 70s. Though the Hồ Chí Minh persona is subjected to different depictions depending to the context and message of the poster, he is always seen with a benevolent smile, white beard and in white uniform - something he wore most during the last decade of his life. Scanning through all the posters with him as the main subject matter or occupying a more symbolic position, I notice two ends of a spectrum: he is either portrayed as larger and more sophisticated than anyone else, in grandeur and with an almost ghost-like presence, or his feature is reduced to the most basic form showing just his head just like a national emblem (see figure 7&8). The latter practice is also evident in the depiction of Lenin and Stalin in Soviet propaganda posters suggesting the indispensable ideological influence of these figures on the state identity.

Figure 1. Eternal gratefulness towards Uncle Hồ

Figure 2. Who loves children more than Bác - Who loves Bác more than us childrenAs someone who always worries about the future of Vietnam - his one and only family, nurturing the next generation of citizen from a young age was one of his top priorities. Appearing as a dominant figure in size, figure 1 portrays him as someone that is capable of affections with him looking at his "niece" with caring eyes, while the little girl, represents the entire nation looking up to him with admiring eyes. The text "Eternal gratefulness towards Uncle Hồ" indicates the greatness of Ho's contribution to the country, at the same time serves as a reminder to all of those who comes across this poster of their duty. In figure 2, though not occupying the most space, he still appears in the centre and his presence is accentuated with the use of pure white paint for his shirt - a stark contrast as compared to the children around him. Racial harmony and collectivism are at play here: he is surrounded by children of different ethnicities they all receive an equal share of love from Hồ. On their necks, everyone is wearing the same piece of red scarves, which is a part of the primary school uniform that is said to be a cut from the Vietnamese flag. The red colour of the flag represents the blood that is running in each of Vietnamese, and so having him and all the children wearing it suggest that everyone is related to him and is equal.

Coming from a scholastic background, together with the time spent in different countries, and his prolific understanding of Marxism-Leninism, Hồ is perceived as a wise leader, whose words do not only hold authority but also wisdom and inspiration. In fact, the name "Hồ Chí Minh" means "Hồ The Enlightended." The quality of the leader and the teacher can be evident in the fact that Hồ had many talented disciples, subordinates and mighty soldiers. Figure 3, with him dominating the entire poster again, depicts how a voice call from Hồ could reassure the soldiers, who are fighting at the battle ground: they all have faith in him and his leadership skills. A word of affirmation from him proves more than enough for the frontline soldiers without the need for him to even be physically present where they were. Figure 4 depicts Hồ in the position of a conductor, which was copied from an exact photograph of him directing an orchestra during the 3rd National Party Congress in 1960.[21] Text in this poster was extracted from the lyrics of the song "Unity", which Hồ was manoeuvering that night. Though his physique was not enlarged like figure 3, rather he stood higher above in an all-white outfit than the female soldiers from three different regions of Vietnam: the Northern, the Central Highland and the Southern. With his eyes looking out of the frame, rather than looking down to where the women were, the poster implies a geographical distance among him and the compatriots, however with his leadership skills and the trust people had for him, he still managed to guide them through.

Figure 5 Bác still marches with us. Image courtesy of Bảo Tàng Quân Đội.

Figure 6 Bravo, the North excels at fighting and producing. Image courtesy of Dogma Collection

Both posters were produced after Hồ's passing. Artists Huy Oánh and Nguyễn Thụ depicted a mass marching through the Hồ Chí Minh trail from the North to the South. Accompanied by a song title by composer Huy Thục, which literally translates as "Bác still marches with us," the poster was made to encourage soldiers to fight with all their might to liberate the South. Instead of wearing his usual attire, Hồ is seen wearing his military uniform, standing prominently in the foreground, looking towards a direction that seems to be the destination - the South. As compared to previous examples, here he seems detached from the background as if existing in a different and mythical realm. Similarly in figure 6, painted in a subdued shade of white - making him stand out but not too strikingly visible (as in figures 2 & 4), Hồ appears at the end of the horizon like an ethereal, heavenly spirit looking towards the North and the text, which reads "Bravo, the North excels at both fighting and producing." This poster, probably made during the nation-rebuild period after the Vietnam War, has the same meaning as the poster in figure 5: even though he has already passed, he will always be there watching over his Vietnam family and every step his nephews and nieces make.

Figure 8. Nothing is more precious than Independence and Freedom

Since the passing of Hồ Chí Minh, the State has consistently and thoroughly carried out the solemnisation of his cult through monuments and cultural productions. In recent years, many scholars and historians have started to bring up Hồ Chí Minh's will in which he specifically had asked for the cremation of his body and modest funeral ceremony. The Politburo at the time said that they had discussed the matter with Hồ and had managed to convince him to let the state embalm his body, so that Southern compatriots could come and visit him after reunification. There was no proper account on what Hồ's response was. As the nation's father, the state was tasked with his posthumous proceedings. However, having the agenda to maintain his cult for political and propagandistic purposes, he was denied of the traditional treatment native to any Vietnamese such as proper burial and death anniversary celebration based on Lunar calendar. Furthermore, it is his birthday that gets widely celebrated every year rendering his death anniversary less of an important occasion. Altogether, the state commemorative process inevitably denies any posthumous metamophorsis making his spirit forever stuck in the world of the living. Until recently, the portrayals of Hồ as the nation's deity and ancestral spirit, and as emblems can still be seen in contemporary propaganda posters and billboards. However, after years of staying true to one person and a single-story plot, his cult has started losing its ramifications amongst the local youth - through contestations of his corpse and the maintenance work required each year, as well as the ongoing extravagant race among provinces to build the next biggest monument in his name. The state, probably being aware of such situation, however, finds themselves again stuck in an awkward position as after Hồ Chí Minh, for many years they have yet able to groom a successor, thus having no other choice but continue with the [outdated] solemnisations of Hồ's cult.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bảo tàng Quân Đội. (2002). Sưu Tập Tranh Cổ Động Ở Bảo Tàng Quân Đội. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản Quân Đội Nhân Dân.

Bayly, S. (2019). The voice of propaganda Citizenship and moral silence in late-socialist Vietnam. Terrain Anthropologie & Siences Humaines.

Lu, X., & Soboleva, E. (2014). Personality Cults in Modern Politics: Cases from Russia and China (CGP Working Paper Series). Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, Center for Global Politics.

Dror, O. (2016). Establishing Hoˆ Chí Minh's Cult: Vietnamese Traditions and Their Transformations. The Journal of Asian Studies Vol.75, No.2, 433-466.

Bello, W. (2007). Introduction to Hồ Chí Minh: Down With Colonialism! New York: Verso.

Schreiner, K. (2017). Comparing Aung San and Hồ Chí Minh: The Making of a Cult of Personality. University of Saskatchewan Undergraduate Research Journal, 3(1), 6.

Pham, T. H. (2020, May 21). Re-examining the Cult of Personalities: A Comparative Cross-National Case Study of Kim Il Sung, Mao Zedong, and Hồ Chí Minh. Atlanta, United States of America: Georgia State University.

Quinn-Judge, S. (2002). Hồ Chí Minh: The Missing Years. United States: University of California Press.

Brocheux, P. (2007). Hồ Chí Minh: A Biography. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hồ, C. M. (1947). Gửi bác sĩ Vũ Đình Tụng" [Letter to Dr. Vũ Đình Tụng]. Letter.

Dror, O. (2007). Cult, Culture, and Authority Princess Lieu Hanh in Vietnamese History. University of Hawai'i Press.

Kurfürst, S. (2011). Redefining Public Space in Hanoi: Places, Practices and Meanings. Dissertation for attaining a doctorate in Southeast Asian Studies, University of Passau, Passau.

Nguyen, H. N. (2018, December 22). "Uncle Ho's soldiers" - an undeniable Vietnamese military cultural value - National Defence Journal. TCQPTD. http://tapchiqptd.vn/en/events-and-comments/uncle-hos-soldiers-%E2%80%93-an-undeniable-vietnamese-military-cultural-value/13025.html.

McHale, S. F. (2010). In Print and power: confucianism, communism, and Buddhism in the making of modern Vietnam (pp. 105-107). book, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

HOÀNG, Ð. Á. N. G. K. I. M. (2007, May 15). Bác Hồ bắt nhịp bài ca kết đoàn. Nhân Dân Điện Tử. https://nhandan.vn/di-san/bac-ho-bat-nhip-bai-ca-ket-doan-416459.

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.