“Am I Superwoman?” is an an exhibition initiated by the Dogma Collection and curated by Nguyen Phuoc Bao Chau

Exhibition booklet available here

———

“In a raw, sarcastic outburst unlike her usual well-composed self, she asks:

“AM I SUPERWOMAN?”

…

Despite the provocative appeal, what this question really calls for is not a straightforward answer, but an invitation to peer into the complex, mythical construct of feminine roles. Unraveling it through an art exhibition does not sound like a bad idea, does it?

“Am I Superwoman?” in one aspect, retrospectively analyses the glorifying portrayal of Vietnamese female figures in Vietnamese Socialist idealism possessing the Ba đảm đang[1] virtues (‘dutiful Home-maker, Worker, and Fighter); and in the other, introspectively delves into the intimate interpretations of femininity by contemporary female artists. The artists’ multidisciplinary works serve to explore woman sacrifice, defiant efforts to redefine individualistic feminine values, and ponder over the outsiders’ gaze on the female body. Bringing the two together allows a comparative reflection between myth and reality, collective idealism and personal characters concerning female roles.

One prominent feature of the show is historical propaganda posters, a popular medium for the Vietnamese government to promote the “good ways of life”. Through the years, they have served to instill an ideology of femininity by means of pre-existing sociological context. Through out the exhibit, selected posters present the Ba đảm đang women in pursuit of the ideal life. They project the female body often as mysterious, young, voluptuous and robust, despite the most arduous circumstances. In them, we see the manifestation of an “organized myth” (Ellul, 1973), which combines with the pretext of deep rooted Confucian teaching of Tam Tòng Tứ Đức[2] for every “good woman” in Vietnam traditions, which helps make it so powerful a concept that it penetrates every corner of consciousness and becomes reality. This type of sociological propaganda works slowly and gently, introducing an ethics in benign form, but it ends up “creating a fully established personality structure” (Ellul, 1973, p. 66), which is hard to dislodge once established. Modern time in Vietnam has emancipated women in various measures, but does the Ba đảm đang ghost ever stop haunting?

Today, women earn merits far and wide outside of their homes, but at the same time, still carry with them the responsibility to hold together the nooks and crannies of the domestic sphere, to bear and rear children, to be a benevolent, refined domestic goddess. Watch any TV commercial for household products and one can easily find happy, polished women effortlessly changing roles between work and home, singing serenely: “A smile will always radiate on my face….”. In “Woman, native, other”, Trinh T. Minh-ha writes: “They have made of us heroic workers, virtuous women. We are good mothers, good wives, heroic fighters… ghost women, stripped of our humanity.” If Minh-ha’s humanity encounters the immaculate female figures in propaganda, does it wonder: Do they have fear and weaknesses? Do they suffer from pain? Do they ever let their messy hair down and show their quirks? Do they, in flesh and bone, truly aspire to be superhuman?

In response to these questions, the contemporary artworks of the female artists display their own realities and distinctive beliefs. Their artistic labour diverges into different styles of expression that embody individual subjectivities and characters.

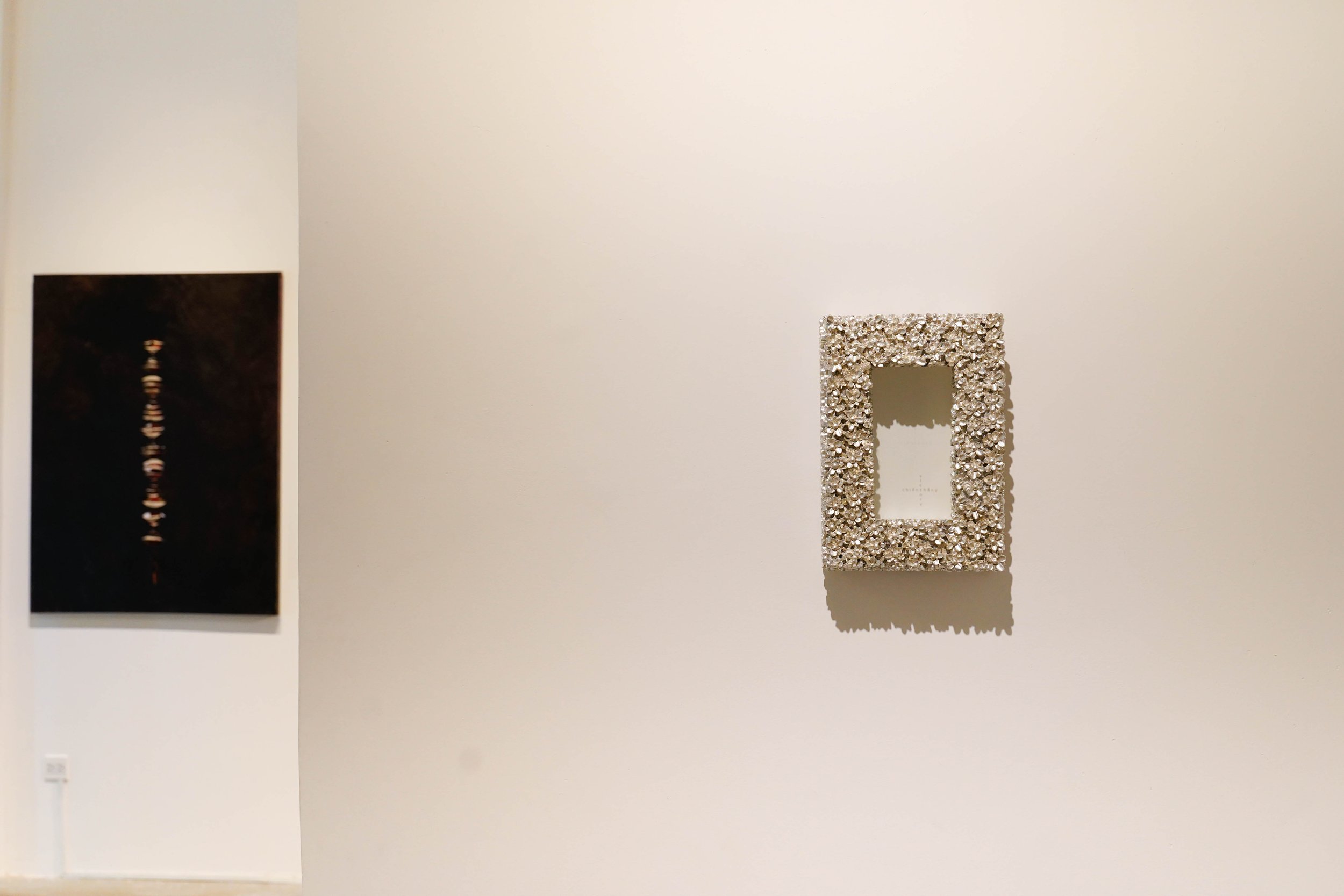

Ngô Đình Bảo Châu’s act of stripping away vibrant colors and pulling apart a sculpture that she installed ten years ago, named “Victory” to celebrate female heroism, reflects her personal evolution and conscious attempt to decline the given virtuous titles she no longer aspires to bear. With hindsight on this work, Châu transitions to her present endeavor to destroy that very same victory. More precisely, to destroy every image, every conception that has defined that honor, which has also been a guise of nameless domestic chores, unwieldy responsibilities delegated to women everyday.

Gone was a decade. What remains of a sacred monument are scattered mementos: a carved wooden frame carrying memory that has seemed to fade away – a modest shrine; a commonplace neon signboard reminiscing an expired item – a deconstruction of a pedestal. Such are reminders of earthling mortality, of mourning, of mundane life and a claim of an irony: relentless pursuit of elevating a symbol to new height whilst shouldering a hefty burden – a rejection of a title! Such is Châu’s inquisition into the realm between symbolism and truth, between illusion and authenticity, in the manners that certain hero/ine are presented, as seen in propaganda, where mystified figures are projected onto real bodies. Châu’s application of printing technique, minimal wording and fluorescent light also mimics the effects of mass reproduction, advertising and slogan in propaganda.

As the dualities play out before our eyes, we eventually come to realize that Châu’s work mirrors the back of a propaganda poster, the hidden place where the badge of honor is being negated to allow for secret codes to transmit and discreet anonymity to illuminate.

Lêna paints women but seemingly from the inside out. Turning their emotions and psyche into elementary forms, akin to pagan symbols of fertility and femininity, and with a structure that emits both pain and power. Her subtle visual language and abstract thinking is indeed a lucid choice to break free from pre-conceived notions of the female corporeal forms.

Three paintings, almost like a triptych, one white with hints of hot pink, one black layered on a deep red, and the last one—a layer of white fog over strokes of warm and dark colors, evoking flesh and blood, and passion. They are simple yet moody. The surfaces are cut and stitched in patterns that appear and disappear, like moon rhythms, ripples on a surface, mouth speaking or trying to speak, sound waves traveling, etc. There is something logical yet sensual about them, and in some parts also vulgar and tortured.

Coupled with the paintings is a site-specific installation inspired by the mythical Andromeda—tied to a rock as a sacrifice because of her beauty. The story is told by the Greek as part of the myth of Casseopia, the queen who angered the Nereids, sea nymphs, by boasting that she and her daughter were more beautiful than them; and part of the myth of Perseus, the hero who saved her from the sea monster Cetus. What Andromeda thought was never mentioned.

As one of the few constellations named after a woman, she is frozen in the sky forever in the state of being tied to a rock. Drawing her constellation on window blinds that shade the space with punctures, allowing light into the space and the viewers to peek through and see the outside world, perhaps is a small act of setting Andromeda free. And for those who wander out onto the balcony, they can discover small fragments of thoughts by contemporary women.

They may, then, also wonder about the dilemma that Andromeda faces: abide by her Father, the King Cepheus’s command[3] in exchange for a horrific death, or take flight. The legends being written about Andromeda or comparable females have not tackled this perplexing aspect. Similarly in propaganda, instead of complicated truth, simple pictures are provided, combined with pre-existing myths, to validate painful and severe actions as simply good, just and true. This is why the propaganda slogan of “Giặc đến nhà đàn bà cũng đánh” (Women fight off any enemy at their door) becomes incredibly unquestionable.

In Xuân Hạ’s kinetic sculpture inspired by the story of Mẹ Nhu, a National Heroic Mother, starkly contrasting with the cold, permanent materiality of stainless steel is the emotive memory of warm blood flowing out of Mẹ Nhu’s frail body when she attempted to protect her children. Unlike Andromeda whose life was eventually saved, Mẹ Nhu was immediately shot dead by the enemy. She would live on as an immortal but little would ever be known about her life, her private agony or mortal happiness as a mother. Xuân Hạ’s playful depiction of Mẹ Nhu’s children, much unlike the solemn, imposing public monument[4] that portrays her, is not only an endearing tribute, but also an embodiment of her private questions: “Between the grand title of a national heroine and being an unsung mother of her children, what would Mẹ Nhu have chosen?”

The artist continues her narration by tackling the topics of “mother”, “symbol”, “monument”, “honor” and the omission of inconvenient truth in the process of chiseling into an exemplary figure such as Mẹ Nhu for the public eyes. Two abandoned stone carvings caught her attention. These found objects are rejected marble sculptures from an atelier specialized in producing revered spiritual idols. Suspended in unfinished states, they resemble phantomlike enigma, colorless kaleidoscopic shapes. A dove? Virgin Mary? A female deity?... As much as they are ugly and undesirable in ideal standards, they are alluring in Xuân Hạ’s aesthetic, because they touch on her lingering concern about the actual accounts of the women trapped behind the personification of fabled forces. Hence, she deliberately cut through the aura surounding divine figures to point out the violent intervention on the fragile women, those who sacrifice their own ephemeral flesh to model for permanent, imperishable structures for generations of strangers to admire.

While the kinetic sculpture expresses Xuân Hạ’s unique observation, the found stone objects tell stories in unconventional tones. They expose the vertical, top down power dynamic between the creator and the objects. The creator determines the good, the bad and the ugly and ultimately influences public acceptance. At stake are the real, often challenging records of the persons in question.

To create a deity, the creators, namely, sculptors and propagandists enjoy the same authority. They both decide on the stereotypes that are enforced by symbols and ready-made judgments to spare the audience the trouble of visualizing for itself. Plump lips, refined nose, round hips, slim waist, bit by bit, the creators are manipulating perception and attitude toward the archetypal forms and symbols. In turn, symbols are related to the psychological phenomenon of the stereotype, that which empowers propaganda and art to take over literature, past and present, and history, which can be rewritten according to specific needs to influence beliefs. Propaganda in a sense works like an aphorism, in that it simplifies a complex truth for public consent.

Regardless of individualistic expressions, the three artists unite to dissect the organized myth, the constructed [super]woman with their differentiated views. Notably, their works are far from discrediting the virtue of innate sacrifice and love of a woman for her immediate family and other human beings, but to make way for personal deliberation that such love is an unconditional choice, not an obligation.

“Am I Superwoman?” also invites the viewers to join and to continue this female narrative in the present context: Has time changed, or is it still an on-going negotiation with the past, as we transcend into the future?

…

[1] Ba đảm đang: (i) Đảm đang lao động, sản xuất, công tác, (ii) Đảm đang gia đình; (iii) Đảm đang công tác hậu phương bảo vệ Tổ quốc (Instruction from Vietnam Women Association, 2010)

[2] Tam Tòng (Three principles of obedience) – Tại gia tòng phụ, xuất giá tòng phu, phu tử tòng tử – As a child, she obeys her father; as a married woman, obeys her husband and as a widow, obeys her son.

Tứ đức (Four virtues) – Công dung ngôn hạnh – A “good woman” must be skillful in her work, modest in her behavior, soft-spoken in her speech, faultless in her principles. Strays from any of the virtues and she is a “bad woman”.

[3] Poseidon floods the Ethiopian coast and sends a sea monster Cetus to ravage the kingdom because of Casasseopia’s arrogance. In desperation, King Cepheus consults the Oracle, who announces that no respite can be found until the king sacrifices his daughter. Andromeda is thus chained to a rock by the sea to await her death.

[4] The national public monument of Mẹ Nhu now stands in a grand manner at the gateway to Đà Nẵng City, the hometown of Xuân Hạ.